Polyrhythm Explained: What is it & How to Use it Creatively

Polyrhythms are found throughout all genres of music and can add an exciting new element to our songwriting and invigorate our creativity.

What Is A Polyrhythm?

A polyrhythm is when two different rhythms are played simultaneously and perceived as one. The “syncopation” of different rhythms will generate different accents and subdivisions of time, while the added notes will make a beat sound denser and more complex.

A Brief History of Polyrhythm

Polyrhythms found their way into Western music mainly through the influence of Sub-Saharan African music. Complex African rhythms were carried to the Americas and consequently evolved into Afro-Cuban music as a consequence of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

This had a profound impact on Western culture and American Jazz. David Byrne of the Talking Heads hypothesizes that the wide-open plains of the desert gave birth to polyrhythms because the space doesn’t echo. The density of polyrhythmic music could never have evolved in a closed space without sounding like a total cacophony!

Now that we understand a bit about the origin and history of polyrhythms, let’s look at the theory and how WE can use polyrhythms to turn up our creativity.

Types Of Polyrhythm

Using polyrhythms, we can take two or more familiar (boring) patterns and combine them to form something new and compelling.

3 Against 2 Polyrhythm:

Polyrhythms are described as “# against #”, with the # being the numbers of notes played over or “against” another number of notes.

The most common polyrhythm is “3 against 2” or “2 over 3”.

The second “poly” rhythm will use two notes for every three notes played by the first rhythm. Make sense?

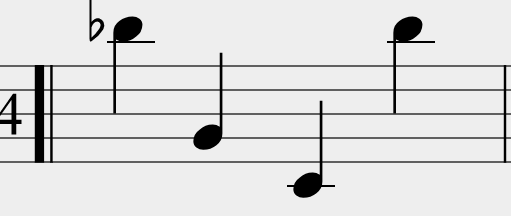

A “3 against 2” polyrhythm in a measure of 4/4 time has steady 8th notes in one figure combined with 8th note triplets in the other. You can see in the notation above how the notes align with one another.

Audio Example (with visualizer):

Polyrhythms typically contain one “rational” and one “irrational” rhythm…

This means that one rhythm will typically be in the form of a tuplet (triplet), quintuple, or septuplet, which is “irrational” because it squeezes more notes into the space of one beat than is usually permitted by the song’s time signature.

The other rhythm will be “rational”, or congruent with the song’s time signature. In the three against two polyrhythms, you’ll notice that the “3” is in the form of a triplet, where three 8th notes are being squeezed into the space usually occupied by just two notes.

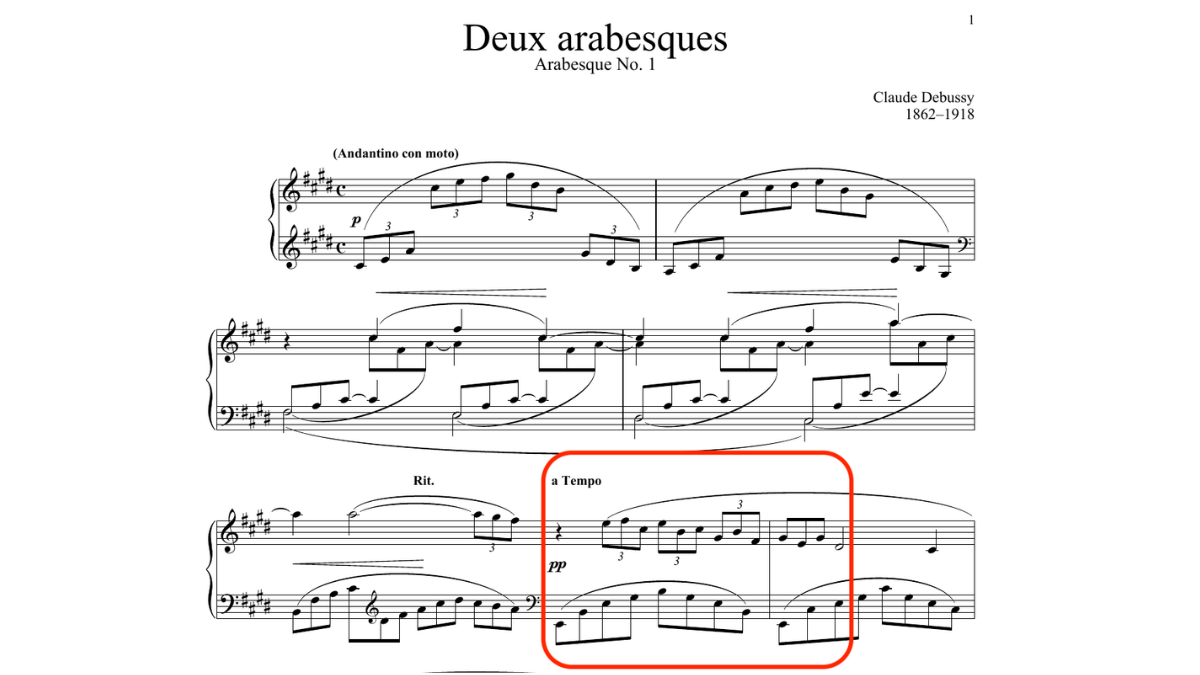

Here is an example of a three against two rhythms used in the music of French composer Claude Debussy:

In measure six of “Deux arabesques”, the composer puts 3 in the right hand against 2 in the left hand. This is a common way to use polyrhythms on the piano.

Sing your MIDI controller, try writing and recording a part with the same rhythm as “Deux arabesques” but using different melody notes. If you’re a writer/producer who doesn’t focus on keyboarding, and it’s too difficult to play the three against two rhythms live, try recording one part at a time on two separate tracks or using non-destructive overdubbing.

You can achieve this on a stringed instrument by slowly practicing playing each rhythm on two separate strings (using a pick and fingers or more than one finger). If you aren’t an accomplished instrumentalist, this can be challenging, so don’t worry. There are other ways to utilize polyrhythms in your process.

One obvious way is to use polyrhythm in the rhythm itself, like a drumbeat or strumming pattern on the guitar. When played against another rhythmic instrument like bass, rhythm guitar, or percussion, it can create a polyrhythm.

We will also look at how to achieve this and create a polyrhythm with an instrument and the voice in the next section.

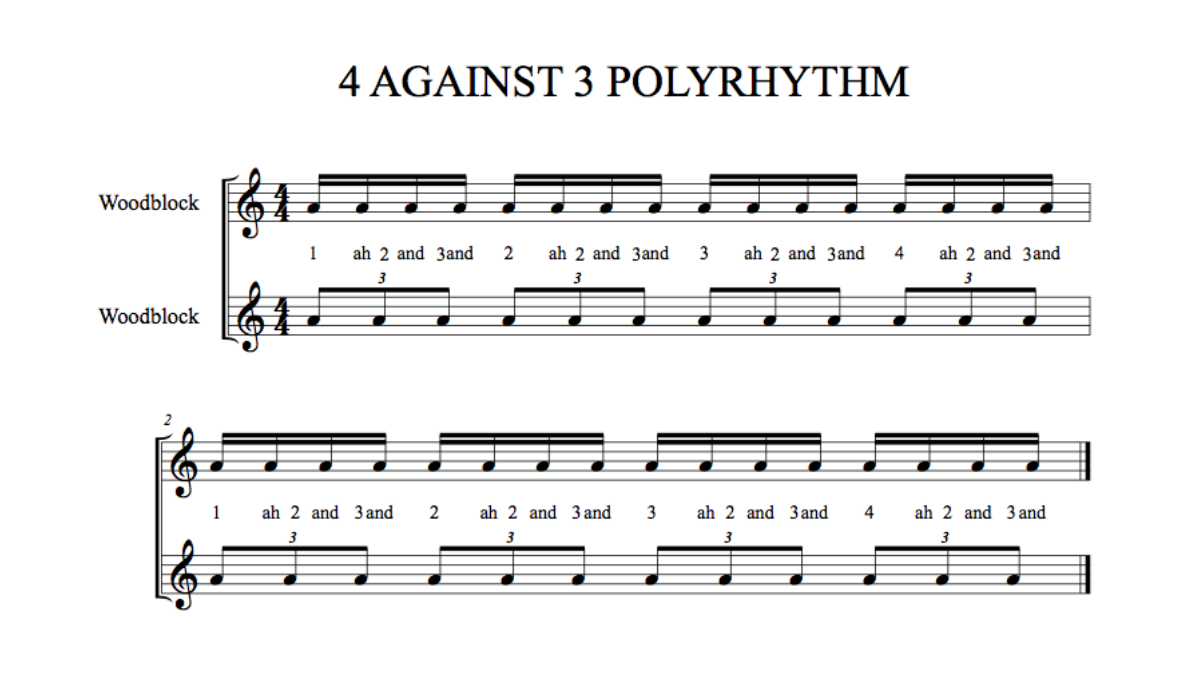

4 Against 3 Polyrhythm:

Four against three is another common polyrhythm by way of Afro-Cuban music, also found frequently in European folk music, Celtic music, and more. Four against three is more commonly used as an actual rhythmic figure as in many contemporary examples of Polyrhythm.

In “4 against 3” we multiply the 2 (8th) note figure from the “3 against 2” polyrhythm so that one triplet is played in the space of four 16th notes.

Here you can hear an example of a four against three polyrhythms in the music of Nine Inch Nails. At 1:22, a 4/4 drum beat enters against the piano part, played in 3/4.

NIN “La Mer”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcIOInVS7jo

If you’re having difficulty hearing or feeling the polyrhythm, try counting one piece at a time. Count, clap, and tap along to the piano in 3, then rewind and do the same for the drumbeat. By isolating each piece, you will begin to intuitively feel how they align, clash, and play against one another.

Here is another example of an extremely fast four against three rhythms found in the music of Tito Puente:

Kendrick Lamar’s masterful “To Pimp a Butterfly” album is known widely for its jazz influence and incredible musicality and contains a great example of polyrhythm used in contemporary hip-hop. In “How Much A Dollar Cost”, a 4/4 and 3/4 pulse co-exist throughout the song.

The implications of this type of polyrhythm in rap are incredibly cool because it gives the MC the ability to lean into or switch between each pulse with their flow. Kendrick’s verses flip-flop between tuplet rhythms and straight rhythms throughout the piece against the 4/4 drum beat. This creates myriad examples of polyrhythms throughout the song.

Kendrick Lamar “How Much A Dollar Cost”:

One way you may use this in your creative process is to program or play a drumbeat in 4/4 and then record a guitar, synth, bass, or vocal part in 3. Try downloading two different samples from LANDR’s Sample Library and loading them into your DAW to apply this concept quickly. Sync them to the same tempo, and voila! You’ve generated your first polyrhythmic creation.

Now add vocals, strings, etc., and you’re well on your way to surprise yourself with new sounds!

We hope this intro to polyrhythms was insightful and inspiring. Don’t forget to keep your rhythmic chops in shape with ToneGym’s “Rhythmania” game. We can’t wait to hear what you come up with!

Comments:

Nov 27, 2025

Login to comment on this post